Candice Breitz

Whiteface

Artist

- Candice Breitz

Curator

- Çağla Ilk

Curatorial assistance

- Sandeep Sodhi

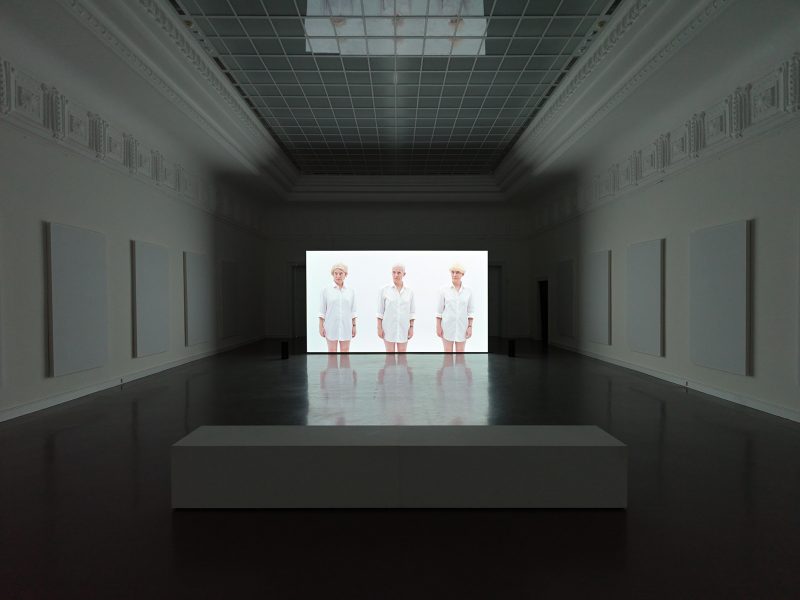

Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden presents Whiteface, the latest video installation by Candice Breitz. Accompanying it is Breitz’s work Extra. Both works deal with whiteness and its hegemonic discourses.

With Whiteface, Kunsthalle Baden-Baden presents a focused solo exhibition by South African artist Candice Breitz. Two video-based installations from the artist’s long-standing oeuvre—Whiteface (2022) and Extra (2011)—are juxtaposed to stimulate conversations around race, privilege and the asymmetrical politics of representation within cultures that have been shaped by white suprematist ideology. The narrative politics of Breitz’s practice, her self-critical and at times satirical gaze, and her experimental approach to media, intertwine with the curatorial vision of Kunsthalle Baden-Baden to challenge conventional modes of thinking and social hierarchies through its discursive program. A symposium on “Whiteness” will offer the public a platform for discussion.

The current transformation of German society through public debates on diversity, gender, and transnational politics also touches on the self-conception of whiteness (and by implication of Germanness) that Breitz unfolds in her new work. In both Whiteface and Extra, Breitz performs and embodies a range of positions reflecting contemporary discourse that addresses racism, discrimination and whiteness in the media, embodying a range of voices drawn from television to news media to the Internet. Her video installations hold up a mirror to society, disruptively paraphrasing the media mechanisms that feed the collective conscious.

Whiteface

The eponymous new installation Whiteface, co-produced with Museum Folkwang, explores the aesthetics of representation, the power of language and the crisis of identity politics, inviting the public into a transparent, open and critical engagement with the self-construction of whiteness, race and the politics of discrimination. In recent years, Breitz has collected and archived a wide range of found footage fragments that document “white people talking about race.” Her archive includes the voices of prominent political figures, news anchors and talk show hosts, as well as those of lesser known and anonymous YouTube bloggers, covering white perspectives that run the gamut from neo-Nazi ideology and far right propaganda to everyday racism and the posturing of “good white people.” In Whiteface, Breitz appropriates and ventriloquizes dozens of voices drawn from this archive, channelling them through her own white body. Wearing nothing but a white dress shirt and zombie contact lenses, the artist conjures up whiteness in a variety of its guises, rotating through a series of cheap blonde wigs as the work unfolds, among which her own platinum head of hair is featured. Breitz’s un-wigged appearance among the characters that populate the piece, serves to acknowledge the artist’s own embeddedness in whiteness.Yet, while Breitz and many of the disembodied voices that she lip-syncs may be recognizable in Whiteface (Tucker Carlson, Rachel Dolezal, Bill Maher, Richard Spencer, and Robin DiAngelo all make vocal cameos), specific white folks are not the primary target of this stinging satire. Rather, it is the condition of whiteness that Breitz seeks to prod into visibility. Additionally, Breitz will show seven single-channel videos from her new body of work, White Mantras, and a series of photographic portraits of the characters from Whiteface.

Extra

Extra was shot on the set of Generations, South Africa’s most-loved soap opera, and the most watched television program on the African continent at the time the work was made. Broadcast since 1994, the year that South Africa became a democracy, Generations paints a picture of the country’s emerging Black middle class against the backdrop of the media industry. Because much of the script is delivered in Nguni languages (isiZulu, isiXhosa, siSwati, isiNdebele), white South Africans—who at this point in time rarely speak indigenous African languages—simply don’t fit into this aspirational landscape. As such, Generations does not include any major white characters in its cast.The shoot for Extra took place over a two-week period in 2011. Once each scene had been filmed for broadcast purposes, an extra take was captured, this time with Breitz visible on camera. Scene after scene, the artist inserts herself into the unfolding narrative; sometimes subtly, sometimes awkwardly and absurdly, always without easy explanation. The resulting footage is simultaneously thought-provoking and cringe-inducing. Breitz’s performative interventions offer a grammar with which to consider the role of white South Africans in the post-apartheid context, providing a slew of gratingly uncomfortable visual metaphors which, over time, render visible the privileges that still very much attach to whiteness. Breitz’s “extra,” a conspicuous white presence that has slipped itself invasively into an otherwise Black cast, is the elephant in the room. The failure of this pale invader to successfully integrate in the fictional landscape that it has appropriated provocatively evokes the real-world heel dragging of white South Africa: in a country that has been so bluntly shaped by white supremacy and colonialism, many white South Africans still opt for the familiar comfort of segregation.While “an extra” is most literally a minor character who appears onscreen insignificantly and for a short period of time, the word “extra” can also be used to describe an element that is external or foreign, one that does not properly belong. Breitz’s “extra” is less a character thanan embodiment of white privilege, a figure mired in self-absorption and self-entitlement, a being that occupies more than its fair share of space. The disproportionate visibility of this mute white body, which greedily leverages attention for itself at the expense of the larger plot, speaks to the violent insistence with which whiteness demands foreground. In reflecting on the discursive operations that underwrite whiteness, Extra returns to questions that are implicit in earlier works such as the Ghost Series (1994–1996), as it anticipates later works such as TLDR (2017) and Whiteface (2022).

Despite their differences in approach, both Extra (2011) and Breitz’s most recent installation Whiteface (2022) can be described as autoethnographic journeys into the heart of whiteness. Viewed together, these performative interventions offer a scathing study of the vocabulary and grammar underlying the condition of whiteness, a critical survey of the posturing and language with which whiteness frames, normalizes, and leverages its power.Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden is dedicating its entire exhibition space to Breitz’s two works—a curatorial decision intended to reveal the white hegemony of German society. By highlighting the ideological conditions of increasing white supremacist violence worldwide—from the storming of the Capitol in Washington to similar events in Brazil to plans for a coup by German right-wing extremists—the works set the stage for white self-criticism.

About Candice Breitz

Candice Breitz (born 1972 in Johannesburg) is an artist living in Berlin. Throughout her artistic career, Breitz has explored the dynamics through which individuals are shaped in relation to a larger community, be it the immediate community of the family, or the real and imagined communities shaped not only by issues of national belonging, race, gender, and religion, but also by the increasingly undeniable influence of mainstream media such as television, cinema, and other popular culture.

Solo exhibitions of Breitz’s work have been hosted by Museum Folkwang (Essen), the Tate Liverpool, the National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa), San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Baltimore Museum of Art, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki (Auckland), Kunsthaus Bregenz, Palais de Tokyo (Paris), Kunstmuseum Stuttgart, The Power Plant (Toronto), Louisiana Museum of Modern Art (Humlebæk), Kunstmuseum Bonn, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Modern Art Oxford, De Appel Foundation (Amsterdam), Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art (Gateshead), Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean (Luxembourg), Moderna Museet (Stockholm), Castello di Rivoli (Turin), Pinchuk Art Centre (Kyiv), Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève, Bawag Foundation (Vienna), Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León (Spain), the Contemporary Jewish Museum (San Francisco), FMAV / Fondazione Modena Arti Visive (Modena), Wexner Center for the Arts (Ohio), O.K Center for Contemporary Art Upper Austria (Linz), The Australian Centre for the Moving Image (Melbourne), Collection Lambert en Avignon, FACT / Foundation for Art & Creative Technology (Liverpool), Neue Berliner Kunstverein (Berlin), Arken Museum of Modern Art (Copenhagen), Blaffer Art Museum (Houston), Void Contemporary Art Space (Derry), EMMA / Espoo Museum of Modern Art (Espoo, Finland), West Den Haag (Den Haag) and the South African National Gallery (Cape Town), among other institutions.

In 2017, Breitz represented South Africa at the 57th Venice Biennale (alongside Mohau Modisakeng). She has participated in biennials/triennials in Johannesburg, São Paulo, Istanbul, Taipei, Gwangju, Tirana, Göteborg, New Orleans, Singapore, Dakar, Melbourne, Cleveland, Sharjah, Aichi, Rabat and Prague. Her work has been featured at the Sundance Film Festival and the Toronto International Film Festival.